Planning For Trees

Gardening is for everyone, and that includes those who want a tree! How can this be? Not everyone has the space for these kinds of big plants. Not so fast-trees also include bonsai and indoor citrus too! Whether you want something decorative, fruiting, or just plain cool, we will help you pick and care for a tree that will thrive!

What To Look For: Location, Location, Location!

Trees are surprisingly delicate plants. Selecting the right plant, planting it at the optimal time, and choosing the ideal location is crucial for a tree to thrive. We’ll first go over site selection. Trees need space both above and below ground. Their canopies need to spread alongside their roots so they can establish themselves easily and live a long time. Keep in mind a tree’s full size before purchasing. If you’re lacking this space, a dwarf tree variety or even a shrub would be better.

Drainage also is important. Most soil in Colorado retains moisture poorly, however there can be areas with poor drainage in any environment. Picking a drought-tolerant tree would be best for soil that poorly retains moisture, the very best being a native tree. For a tree in a wet area pick one that enjoys damp soil, just don’t forget to water during the drier months!

Lastly, sunlight exposure is essential for trees (and generally all plants). Generally, trees need full sun but some don’t like bright hot light and prefer partial shade. Most trees we carry in our nursery will have little information packets attached to their branches about light requirements. If they don’t, our Ricksters are always happy to help!

What To Look For: Healthy Trees Please!

Now we get to the fun part: picking out the tree! Picking a healthy tree will benefit your wallet and the health of your garden or yard. An unhealthy or sickly tree can transmit disease and decay to other plants, so knowing what to look for while shopping is essential for everyone! Tree leaves shouldn’t be wilting, have discolored bark, odd spots, or oddly colored leaves. You shouldn’t buy a tree that has non-beneficial insects, like aphids or mealy bugs, on its leaves, branches, or bark. Trees should have evenly spaced branches and a central branch that acts as the main trunk. The Colorado State Forest Service suggests, “Tree foliage and branches should be distributed on the upper 2/3 of the tree.” Study the tree roots too. Are roots circling, appear pot bound or are suffocating the stem and trunk of the tree? These are all bad signs and this tree shouldn’t be purchased.

Why Natives?

Some trees will do better in Colorado than others. Native trees in particular are hardier and built for our drastic climate. Generally, they will also need less maintenance, like less watering, pruning, and insect control. Natives will thrive in Colorado hardiness zones, though there are always exceptions. A great place to check out native trees and shrubs is at Colorado State University Extension. Alongside pictures, each tab is filled with information about the plant’s preferred elevation, habitat, and more. Click the link to learn more: https://csfs.colostate.edu/colorado-trees/colorados-major-tree-species/

Planting

Trees have specificities when it comes to planting. When you choose to purchase a tree from our nursery, we’ll typically send you home with one of our tree-planting guides. It’s also available on our website, link located here for ease: https://www.ricksgarden.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Ricks-Tree-Shrub-Planting-Guide.pdf .

We want to remind you to NOT FERTILIZE your tree for the first year! This can damage and even kill a tree. Trees are getting established in their new home and this is a stressful time. Applying fertilizer adds unnecessary stress in the first year.

Whether you choose a flowering crab apple or go the native route and pick a tree that easily establishes in our area, finding the right fit tree is what we should all strive for. A chosen tree should be picked to thrive in your yard’s microclimate. Once established, trees return the favor. Providing shade, habitats for animals and birds, cleaning the air and water, and limiting rain runoff are just a few of the reasons a tree can benefit the community. Likewise, trees increase property value and cut noise pollution! Trees are legacy gifts to the environment and to future generations. Whatever your reason is for choosing a tree we’re happy to help you do it right. Happy gardening!

Getting Home & Garden Ready For Sale

Despite mortgage interest rates continuing to climb in the past several months, in this military base-saturated city, we continue to have a thriving real estate market. If you are prepping a house for sale, know that it does not have to be scary! Historically most house sales occur in the spring, so the later winter months are the perfect time to begin thinking about how to improve your curb appeal and get a “to-do” list fleshed out in time for your spring sale. Sprucing up your yard is especially important.

The first thing you should do is take your blinders off. You probably have lived at your house for some time. Pretend you are pulling up to the house for the first time or walk by your house like you are new to the neighborhood. Take notes. Like an artist, you will come back to this step multiple times, building a masterpiece!

- Do you have a couple of ways your eye can “travel” through the landscape? If not, how can you add interest in multiple areas of your yard?

- What are the immediate eye sores? Clean those up or remove them immediately.

- What is the highlight of your home and yard? How can you further accent it?

- What trees or shrubs need to be trimmed?

- Are there holes in the landscape? Can a tree, shrub, ornamental grasses, several perennials, or a boulder fill in the gaps?

The second thing that is helpful to do right now is a general yard cleanup. Even if your yard is ho-hum, an easy way to elevate the place is to do some general yard maintenance.

- Clean pathways/ sidewalks by sweeping dirt/ debris or pulling weeds

- Rake leaves off your lawn. Leaves can be mulched into your lawn also, by running a lawn mower over them.

- Remove any weeds. Pulling is preferred especially now, when they are most likely dead. Feel free to put a natural pre-emergent down, like corn gluten. This will prevent weed seeds from germinating in the spring.

- Pruning should be done in the spring, but take note of which trees or shrubs should be addressed before your sale.

- Consider if outdoor statement containers should be purchased, so you can plant vibrant flowers ahead of putting your home on the market.

- Add a fresh layer of mulch or gravel to refresh any landscaping areas. Do not forget to put a weed pre-emergent down under the mulch and on top of the new mulch, to discourage weed growth. There is nothing more aggravating than completing a clean landscaping job to have weeds pop up in the spring. You can also consider laying down weed barrier fabric under the mulch.

- It should also be mentioned that you should remove any yard art that is specific to your “aesthetic.” You want potential buyers to imagine their own lives when doing a home walkthrough. Pack the garden gnomes away for when you move into your new place!

Next, you will want to address outdoor lighting. If you plan on selling in the spring, you will be hitting the market before it is light in the evenings. You will want to ensure that you make your house feel welcoming as people come to showings after getting off of work.

- Highlight your entrance. This is the most important area to highlight. If you are concerned about light pollution, make sure the light casts downward, instead of out or upward. If you are further interested in reducing light pollution at your home, check out this resource on what light fixtures are best: Click here!

- Other areas to consider lighting include pathways, the address number on your house, and any architecture or plants you want to illuminate.

Finally, consider your plant life. You will not do any planting until spring, but this is a wonderful time to find plants that will fit your needs. In the first step, you identified if your eye traveled through the house/garden lay out, if there were any highlights, and if there were holes in the landscape. As you choose plants to fit these roles, consider the following:

- How much water does it require? Will you be able to ensure it gets the water it needs until you sell? Will potential buyers be turned off by the amount of water that you use? Consider more xeric or water-wise options, if this is the case.

- How much maintenance will it require? For example, many younger buyers are no longer interested in lawns, due to the regular, watering, fertilization, aeration, and mowing that a lawn requires.

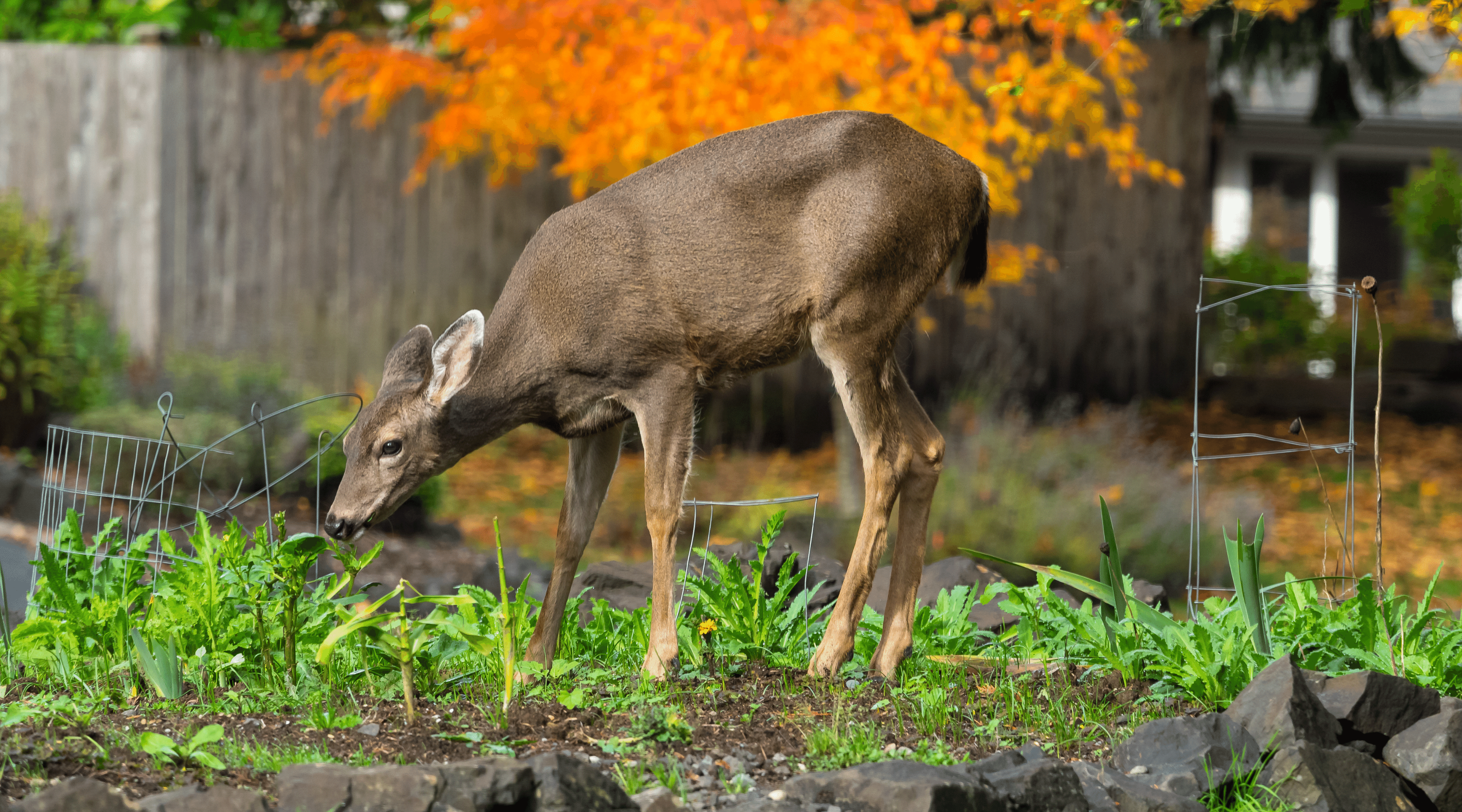

- If you have deer or rabbits in the neighborhood, consider choosing species that are resistant to their munching, so all of your plants look good for your closing!

- Resources that are helpful when selecting native plants or water-wise plants are detailed below:

- Plant Select is a brand of plants that we sell. They have an excellent variety of plants and detailed descriptions of each plant. They specialize in plants that are, “…unique, smart, and sustainable plants inspired by the Rocky Mountain region.” Check them out here: Click here!

- High Country Gardens is another gem of information. They “…offer a diverse and ever-expanding selection of plants for the unique challenges of Western gardens.” Use their perennial filter to drill down to find those difficult-to-find plants that are deer-resistant, in partial shade, water-wise, and good for your zone. Check them out here: Click here!

- Finally, a local resource. Please check out the water-wise demonstration gardens that the Colorado Springs Utilities have. They have two different locations listed below. All of the plants are labeled, which is helpful when you find a plant you have fallen in love with! It is helpful to go visit through the four seasons, so you see how foliage and plants change throughout the year. Check them out here: Click here!

There you have it! Good luck with getting your property ready for sale!

New School Fall Gardening Stretegies

By Katherine Placzek

With fall approaching, many of you are getting ready to put your garden beds and other portions of the landscape to bed. With a more eco-friendly mindset, we would like to suggest a couple of tweaks to your typical routine.

Old school: Raking and bagging leaves, tossing them out for the trash.

New school: Rake leaves from below trees, and use them as mulch around your perennials, shrubs, or on top of your vegetable garden beds. You can also run these over with a lawn mower to mulch them into your grass.

Why: Organic matter, including yard waste, is the most prolific item in United States landfills. Consequently, this unsustainable practice directly contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. Conversely, organic material returned to the soil reduces your environmental impact while providing a useful garden resource. These local sources of organic material and nutrition (from your own yard’s leaves) will feed and insulate your yard all winter long! Decomposing leaf matter enriches the soil, adding carbon and nitrogen to the soil, while plants “sleep.” Leaves also create safe places for native bees and other pollinators. Did you know that almost three-fourths of Colorado’s native bees nest and overwinter underground? Tip: Deeply water the leaf litter in after it has been placed. This creates a wet decomposing mat that will not blow away as easily.

If you have excess leaves that you are not going to be using, please feel free to bring your bagged leaves by our nursery gate (located at 600 N. 18th St. Colorado Springs, CO 80904). This is a community pile that other members come to gather for their own gardening usage.

Old School: Trim any perennials and remove them before the first snow.

New School: Leave all of your woody stalks, leaf matter, and ornamental grasses all winter long!

Why: This allows for winter interest and provides shelter for any hibernating insects. This is especially true for native plants that act as habitat for many native and beneficial insects. Larger life forms, including birds and mammals, will also benefit from grass seed heads left standing, and other plants that provide shelter in the harshest months. If this is unsightly for you, trim your plants, but leave the stems and other leaf matter on the ground to help create shelter throughout the winter. When soil temperature has reached 50 degrees Fahrenheit it’s the preferred time to begin trimming these perennials in the spring, after many insects have completed their wintering cycle.

Old School: Let the winter snows water your outdoor plants.

New School: Water trees, shrubs, and perennials on nice days throughout the winter.

Why: Unfortunately Colorado Springs does not get enough reliable winter moisture to overwinter many plants. This is especially true for newer plants that do not have an established root system yet. Many trees and shrubs, even those that are well-established, should continue to be watered on warm winter days from October through March. When it gets up to 40 degrees Fahrenheit, pull out a hose or dust off your watering can and soak up some of those winter rays, yourself, while you water. Make sure you unhook any hoses after use, as temperatures can cause freezing in the hose bib and other hardware.

Old School: Say goodbye to gardening until spring.

New School: Fall and winter sow, including vegetable and perennial flower seeds.

Why: Many annual vegetables and perennial flowers have a natural cycle where they drop seeds or fruit in the fall. Mimic nature and plant some of your own seeds in the fall to see what comes up earlier and hardier in the spring! In the vegetable garden, this especially works for cold hardy greens. Think spinach, lettuce, arugula, radicchio, etc. For perennial flowers, like wildflowers, it is recommended to put these seeds down in the fall, as many of our native flowers require a cold stratification period. While many people may set up sections in their freezer and fridge for cold stratification processes, direct seeding in the fall eliminates the juggling of space in your fridge/ freezer. Let the ice cream stay where it is!

Old School: Wait until spring to amend any of your garden beds.

New School: Amend your garden beds in the fall so you can plant right away in the spring.

Why: Fall is a good time to test your soil so you know how to amend your beds. Our soils typically fall in the basic pH range here in the greater Colorado Springs area. This can impact how readily available nutrients are to our plants. Do your research and get your soil properly in shape for your spring! Remember that you can also amend with what nature provides; leaves, manure, compost, and other organic matter. These sources do not have a precise N-P-K (macronutrients: nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium), nor spelled out micronutrients (calcium, magnesium, iron, etc) so it is recommended to test your soil in the spring again to see how your soil has changed due to any unregulated organic material. We offer pH and N-P-K, testing in-store, but the CSU extension office also offers a wide range of soil tests.

Now that you know these new school techniques, you might just try other new gardening techniques in the growing season. I know, I know- I am getting ahead of myself! Happy gardening!

Coco Coir vs Peat Moss

By Katherine Placzek

Dear reader,

This article began initially with a straightforward trajectory. I was going to lay out why using peat moss in soil mixes is environmentally harmful and that we all should make the switch to using coco coir. But as I continued my research, I found it was not that simple and the subject required lots of continued digging to find accurate information. Instead, I am going to try to educate you on both substrates to the best of my ability.

Peat Moss:

Why is it used:

Peat moss has an incredible water retention capability- holding 20 times its weight in water. It also has a small but not insignificant amount of nutrients. You can pot a plant directly in peat moss and it will grow due to these nutrients. It is light and fluffy, used by many gardeners to lighten existing soils. It is highly acidic if not amended with lime, and shrubs like hydrangeas or blueberries can successfully be planted into peat. It also can be used as a pea/bean inoculant. It was not until the 1970s that peat became commonplace as a planting substrate for plant people.

How is it harvested/manufactured:

Peat bogs have centuries (possibly more) worth of plants and decomposing peat/sphagnum peat growing and compacting in a dynamic cycle and ecosystem. It is estimated that peat bogs contain more than 44% of all the Earth’s soil carbon and thus are considered a carbon sink (where carbon is stored and absorbed from the atmosphere). Harvesting practices vary in different bogs and countries. The majority of the peat sold in the United States is harvested in Canada. 95% of all peat in Canada is harvested in partnership with the Canadian Sphagnum Peat Moss Association (CSPMA). The CSPMA has strict regulations that they follow, and are involved in many ecological restorations, as well as scientific research behind peat bogs, and the living organisms that use the bogs as habitat. Many of their practices publicize that they attempt to reduce harm, prevent overharvesting, protect habitats, and replant as part of their aim toward sustainability. While this sounds good, in 2021, it was reported that peat harvesting released 2.1 megatonnes of carbon dioxide into the environment. That’s the equivalent emissions of the annual emissions of five gas-fired power plants. Critics also point out that rehabilitated peat bogs are unable to become a carbon-accumulating ecosystem (or a carbon sink) until roughly 20 years after harvesting. Harvesting in other countries is not regulated and they are likely not as concerned with any harm associated with their practices. All harvesting is mechanical due to utilizing fossil fuels. The UK has banned all peat sales for personal gardens beginning in 2024.

Factors to consider:

- Peat bogs house diverse and intricate habitats for all sorts of living organisms. Harvesting, regardless of practice, disrupts this environment.

- Peat bogs are considered carbon sinks- absorbing carbon from the atmosphere. Harvesting peat releases carbon into the atmosphere, causing concern that this practice contributes to climate change.

- Fossil fuels are used in the harvesting process and are used in the shipping of this product to garden centers and other plant/ home improvement stores.

Coco Coir:

Why is it used:

Coco Coir also has a high water retention rate, retaining 8-9 times its weight in water. It does not have any innate nutrients or pH implications, so it is a neutral starting point as a substrate. Coco coir is a waste product from all other food-grade products made from the meat/ milk of the coconut. Before the 1980s, millions of tons of coco coir were left to decompose in large piles, often taking close to 20 years to decompose. Now there is a market for this “waste product,” as a soil substrate.

How is it harvested/manufactured:

Many coconut plantations are based in the poorest countries, Sri Lanka, India, Vietnam, the Philippines, and more recently, in Central and South America and even Mexico. Coconut plantations are often monocultures that reduce natural biodiversity and cause displacement of living organisms. Coconut trees produce a lot of coconuts but do so at the cost of soil degradation. The coconut hull first is soaked in water (freshwater or saltwater) for a long time to break down the fibers on the hull. This process is called retting. The retting process generates water pollution. Among the major organic pollutants are pectin, fat, tannin, toxic polyphenols, and several types of bacteria including salmonella. While scientists are experimenting with treatment options, there does not seem to be a broad-scale accepted solution at this time. This wastewater is often returned to the local community’s water supply or the ocean. Then, either the coconut hulls can be highly processed through mechanical mastication, or beaten and broken down further by hand. This manual process creates a lot of dust, and workers are typically not provided any PPE (Personal Protective Equipment). Reports indicate an increase in respiratory illnesses in communities with coco coir processing. Many of the following processes, if mechanized, are achieved with fossil fuels. There are currently no regulations on the industry’s standards. I also found conflicting information on whether a second rinse with chemicals is necessary, so that is an additional set of pollution outputs to consider. In general, it’s harder to find reputable sources explicitly sharing information about coco coir. This makes me concerned about the transparency of the industry, as well as possible offenses that are intentionally hidden from the public’s knowledge.

Factors to consider:

- Many coconut plantations are monocultures, created by destroying native habitats for diverse organisms, thus causing soil degradation.

- Pollution of the environment due to wastewater from retting processes.

- The lack of regulations concerning this product allows for humanitarian abuses to occur, including health hazards for workers and the surrounding community.

- Fossil fuels are used in portions of the manufacturing process and in transporting this product to your local garden center.

I think continuing to use coco coir or peat moss warrants extra research. Dig into the companies that you are supporting. Do they have certifications, and third-party ratings that indicate that they care about their staff’s health and wellbeing? The environment and the community they impact? Their carbon footprint? Other points that you are passionate about?

All of this makes me consider, there have been gardeners and plants people before me who did not have access to these substrates. What did they use before? Compost. Manure. Leaves. Green manures/ cover crops. Aged forest products (humus). Straw. None of these probably have the water retention that peat moss or coco coir boast, but they all have higher nutrition, which means prior plants people did not have to fertilize in the same manner that we do when we utilize a peat or coco coir base. Many of these local inputs are also free. All of this is interesting and will lead to further research on my part.

The most honest conclusion that I can make is that, when we are removed from the product we are buying, we also become naïve of the ultimate cost and any negative impacts of the product. Perhaps, the point here is to grow plants that are acclimated to our growing habitat (for instance, native plants do not need peat or coco coir to thrive), or to build soil from what nature provides in our local vicinity. While this is easy to say, it is harder to do. I think this new knowledge is powerful, though. We can always experiment and try new things in hopes of finding replacements that have a lesser negative impact. Good luck with your own decisions ahead of you!

Soils that we carry that do not contain peat moss or coco coir:

Back to Earth-

- Composted Cotton Burrs (Acidified and Non-acidified)

EKO-

- Clay Buster

- Top Dressing

Happy Frog-

- Soil Conditioner

Rocky Mountain Soils-

- Top Soil

- Humus

- Compost Cow

- Tree and Shrub

Yard Care-

- Soil Pep

Note: We also carry a variety of only coco coir or only peat-based soils, if you decide you prefer one over the other.

Resources to utilize in your own research:

I think that Gardener Scott (A gardener in CO, who has an excellent library of YouTube videos on vegetable gardening) has a comprehensive video on the pros and cons of both of these substrates.

The link to the website that Gardener Scott references: https://www.gardenmyths.com/coir-ecofriendly-substitute-peat-moss/

Canada’s National Observer on the carbon footprint of peat harvesting: https://www.nationalobserver.com/2023/07/07/news/canadas-carbon-storing-peat-digs-climate-dilemma#:~:text=According%20to%20Environment%20Canada%2C%20about,of%20growth%20within%20those%20sites.

21 report on carbon sinks and greenhouse sources in Canada: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2023/eccc/En81-4-2021-1-eng.pdf

A Q&A with the Canadian Sphagnum Peat Moss Association (CSPMA):

The CSPMA’s website (includes the history of peat, how their manufacturers harvest peat, industry reports, and more) https://peatmoss.com/

Generalized information on how coco coir is made: https://www.madehow.com/Volume-6/Coir.html

Another source on how coir is made: https://coir.com/utility/how-to-make-coconut-coir-the-manufacturing-process/

A study linking coco coir to impaired respiratory function: https://www.thepharmajournal.com/archives/2023/vol12issue3/PartAR/12-3-455-522.pdf

Protecting Our Watershed While Gardening & Landscaping

By Katherine Placzek

Every item that we use in our green spaces– fertilizers, pesticides, sprays, powders and granules, etc. all make their way into the water, after it rains or when we water our plants. This means a myriad of compounds, organic and synthetic, are making their way in our or someone’s drinking water. Yes, most of our drinking water is filtered, but this also impacts lakes, streams, aquifers, wells, and other sources of water that can be a habitat for other living organisms, big and small. While this may feel overwhelming initially, we have the power to make little meaningful changes in the way we manage our landscapes.

Lawn and Garden Fertilization

Three things make a difference here. Quantity, quality and timing:

Quantity: When you use fertilizer, always use the instructed amount of fertilizer or a diluted/ lesser amount. This ensures that your plants can take up the applied fertilizer and that excess is not making its way into our waterways. Excess fertilization can stress plants and negatively impact water quality. Over fertilizer use through agriculture, golf course maintenance, and community landscaping have contributed to dead zones in waterways. A dead zone is where all aquatic life ceases to exist. First, expansive algae blooms occur that crowd out sunlight, which choke oxygen out of the environment, causing inhabitable levels for any life, plant or animal. While some dead zones do occur naturally, the second largest one in the world is in the Gulf of Mexico, where many of North America’s waterways meet. This dead zone is widely attributed to human causes.

Quality: When choosing a fertilizer, it is advisable to read the ingredients, similar to reading food labels. If you cannot recognize an ingredient, know it is likely synthetic. Not all things that are human made are bad, but do your research. You may decide that you do not want some of these ingredients in your garage, home, yard, and local ecosystem. This is why Rick’s is proud to continue to carry our Organic Lawn and Garden fertilizers. Both of these are gentle fertilizers, with low nitrogen levels, and contain ingredients such as chicken manure, bone meal and blood meal.

Timing: Never fertilize before a severe rainstorm where run-off can take the majority of your fertilizer downstream. This is also cost prohibitive. If you plan on putting fertilizer down before predicted moisture, consider prior to a snowfall, where the melting snow can bring the fertilizer into the ground gently. Also read the instructions. Many fertilizers recommend a fertilizing schedule. Follow this, or see if you can stretch the schedule out further, to reduce the amount of fertilizer that you have to buy and apply throughout the year. Never fertilize more than what is recommended, this can stress the plant, and excess product will be absorbed into the waterways.

Pesticide Use

Pesticides include insecticides, herbicides, and fungicides. Similar to fertilizing, follow the same wisdom regarding quantity, quality and timing. We have said it before, but just to remind you: “While pesticides are convenient and sometimes necessary especially when mitigating invasive plant species, pesticides negatively impact pollinator numbers…. It is important to remember that while applying control products at night can reduce pesticide exposure to several pollinators/ beneficial species, this does not protect nocturnal pollinators such as moths and bats. When we use pesticides there is no current method that does not negatively affect pollinators or their second tier predators, who are further up the food chain (Excerpt from our March 2024 newsletter).” All of these pesticides reach water sources that are drinking water for pollinators and larger organisms: birds, fish, fox, deer, etc. Many of the chemicals used in popular pesticides, including glyphosate do not break down with water. This means the problem is washed downstream, but never away, and can exist in our waterways indefinitely. Manual removal of weeds is no fun- we all know this. When we choose conventional pesticides, we give up clean water. Limiting the amount of pesticides we use in our yards is one step to keeping our watershed less polluted.

General Maintenance

When you mow your lawn, consider mulching the cut grass instead of bagging it unless you use the cut grass in your compost. Mulched grass that has been chopped by the mower multiple times and is spread evenly over the lawn acts as a wonderful additive of organic material to the soil. This method improves water retention, and overall soil health, decreasing your need for fertilizer. If you mulch the cut grass, but leave large clumps of thatch, this can burn your grass and be swept away into a waterway. This process can act similarly to over fertilization, causing algae blooms downstream. Use the same logic with fall leaves. Mulch leaf litter and either use it on your lawn or in your garden, to add nutrition to the soil. Avoid abandoning leaves in gutters, and storm drains, as it increases excess nitrogen in the watershed. In the winter, make sure you are using a low saline and non-toxic ice melt as well. Water guardianship takes place in all four seasons!

Plant Selection

Finally, the fun stuff! Select plants and grasses for your landscape that are resilient to the Rocky Mountain circumstances. When we do this, we automatically reduce the need for mowing, fertilizing and the use of pesticides. Native plants especially, have been living here in the Colorado landscape much longer than any human lifespan. They have been taking care of themselves without any of our human care measures, such as fertilization, and will continue to do so into the future. I believe that by choosing to plant native plants in a landscape, you are actually simplifying your overall workload in the yard. You will fertilize less, you will use pesticides less, and regarding grass, you will mow less. That means more money in your pocket and more sitting on the back porch, sipping on a cold beverage. Cheers!

Rick’s Deep Freeze Guide

In preparation for our first deep freeze coming this Sunday, Rick’s Garden Center would like to remind our fabulous customers to take some steps beforehand to help your plant friends and tools out.

- Water in outdoor trees, shrubs and perennials and cover root balls with mulch. Do not mulch up to the trunk. Moist soil conducts earth heat better than dry soil. The mulch will help keep in the heat and protect the sensitive root ball.

- Rose bushes, mulch up to the graft union at the base of the rose trunk. You can use a rose collar or just pile up mulch up to and above the graft union. The graft union will look like a bulging area on the main trunk just above the soil line.

- Bring in any tropical plants, cacti or succulents that are not at least a zone 5 inside.

- Check and move any plants that are blown on by heat vents. This will dry out the foliage in no time!

- Outdoor trees, shrubs and perennials planted in pots should be insulated with burlap bags or mulch and placed against a south or west wall of your home. Avoid watering these before the freeze.

- Water in newly established lawns and grass.

- Go ahead and plant those mums you bought in the ground.. They may come back next year!

- Disconnect and drain all hoses and drips lines from spigots

- Cover newly planted bulbs with leaf, needle or straw mulch.

- Blow out that sprinkler system!

- After the freeze, you do not have to pull up all of the dead material, so that pollinators and other insects have a place to overwinter.

Bare Root Fruit Trees

What are bare root trees?

Bare root trees are harvested from their growing beds in the late fall, and the soil is removed from their roots. They are kept in cold storage over the winter, and planted before they break dormancy in the spring.

What are the advantages of planting bare root trees?

Improved Tree Health

Bare root trees are not grown in a container. This eliminates the industry-wide problems of circling and girdling roots that develop in container-grown stock, a major threat to even healthy-looking plants. Also, since bare root trees are planted early in the spring before they leaf out, the trees get a head start on developing strong root systems in the native soil before they start producing leaves, flowers, and fruit.

Light Weight & Reduced Environmental Impact

Bare root trees are much lighter when shipped. This saves on freight and fuel and makes them easier to maneuver while planting.

More Cost Effective

Shipping bare root trees is much less expensive, and that savings is passed directly to the customer. Our trees will be comparable in size to a #5 container tree, but for half the price! (All trees will be a minimum of 5/8th inch caliper.)

We are excited to offer bare root fruit trees at Rick’s this spring! We are working hard to bring you the best fruit trees possible.

Excellent Quality

The bare root fruit trees we are selling will be of superior quality! We chose to source these trees specifically from growers who supply professional orchardists. Van Well Nursery is based in Washington state and works with several orchards in the Palisade, Colorado area. They have an excellent reputation among professional growers, and we’re excited to offer that level of quality in Colorado Springs! We have consulted with Van Well to bring you the best in bare root fruit trees for our local climate.

Exceptional Rootstock

Since their seed is not true to type, fruit trees are produced from cuttings. Many species of apples, pears, and plums do not root easily from cuttings, so they are grafted onto rootstock grown specifically for this purpose, a practice dating back over 2,000 years.

When purchasing any fruit tree, it is important to inquire about the quality of the rootstock. For our bare root trees, all apples are grafted onto EMLA 7 rootstock. This rootstock is semi-dwarfing, meaning each variety will grow about 50-60% smaller than typical, which is perfect for backyard orchards. This rootstock was chosen for its cold hardiness and extreme resistance to fireblight. The plums are grafted onto a peach seedling rootstock.

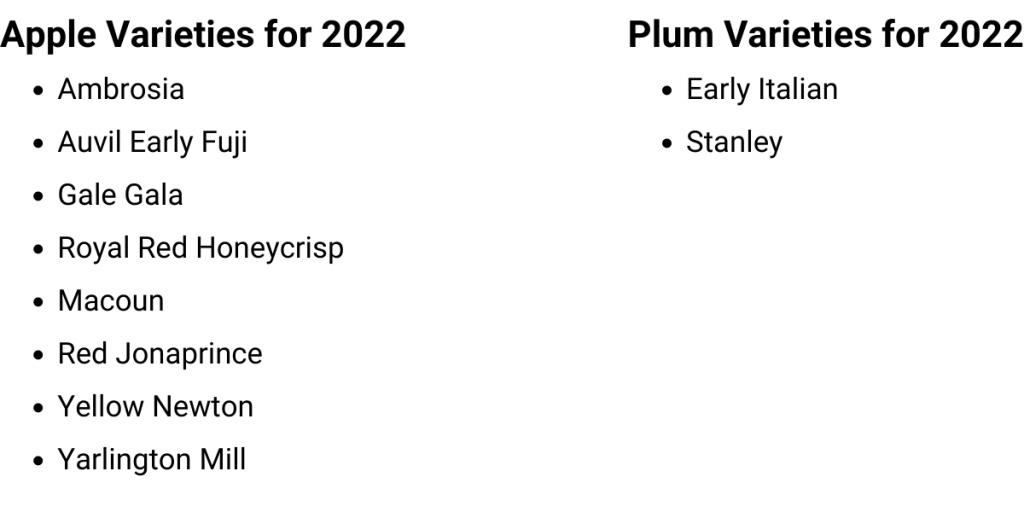

Interesting Varieties

This year, Rick’s will have eight kinds of apples and two kinds of plums to choose from. We will have heritage apples like Macoun and Yellow Newton, and some new arrivals like Ambrosia and Gale Gala. We even have an apple variety that’s used for cider, Yarlington Mill, which arose from a chance seedling discovered in 1898! The plum varieties are both European plums and are very cold hardy.

It should be noted that all apples need another apple (or fruit-bearing crabapple) of a different variety to cross-pollinate. Both types of plums that we carry are semi self-fruitful, but they will bear a heavier crop with a different plum cultivar nearby to cross-pollinate. The two plum varieties we will be carrying will cross-pollinate with each other very nicely. For fruit trees to cross-pollinate, they should be planted within 100 feet of each other.

Cost and Availability

Each bare root tree will be $39.99 and will be sold on a first come, first served basis.

The trees will be arriving in early March, weather permitting. We will continue to sell the bare root trees until they start to break bud, most likely in early April.

If you would like to be notified when the bare root trees become available, please email us at info@ricksgarden.com or call the store at (719) 632-8491 to be put on our notification list.

Timing and Handling

Timing is important when purchasing and planting bare root fruit trees. Bare root trees can only be planted in the early spring. Bare root trees that are planted after they leaf out have a much lower survival rate.

Proper handling is crucial for bare root stock. Roots should never be allowed to dry out – even five minutes of sun exposure on a warm day can do life-threatening damage to the tree. When you purchase a bare root tree from Rick’s, you will be provided with a burlap sack and wet mulch (or other means) to protect the roots during transportation.

The tree should be planted as soon as you get home from the nursery. If you will not be able to plant the tree immediately, please talk to our nursery staff so they can advise you on proper storage procedures.

Planting

Planting bare root trees is very similar to planting trees that have been grown in containers. The most important thing is to not plant too deep; you should have a structural root within the first one to two inches of soil. Amend soil to a maximum ratio of one part compost to four parts native soil. Cover the planting area with three inches of mulch, taking care to not contact the trunk. Staking may be necessary depending on root spread, soil type, and wind exposure.

Protection

Young trees that are small in diameter are the perfect size for deer to rub their antlers on. If deer graze in your neighborhood, cage trees immediately after planting. Trees left unprotected for even one night can be terminally damaged by deer.

For additional tree planting resources, please visit:

Tree & Shrub Planting Guide by Rick’s Garden Center:

The Science of Planting Trees by CSU Extension: https://cmg.extension.colostate.edu/Gardennotes/633.pdf

Winter Watering on the Front Range

Our often dry, windy winters here on the Front Range can be especially tough on landscaping plants such as perennials, trees, shrubs, and lawns. Most plants need moisture throughout the winter to prevent root damage, so developing a winter watering schedule can help to protect your landscaping.

If roots are damaged over the winter, the “winter kill” is not obvious until summer. A plant or lawn may green up nicely in the spring, but in the first hot days of summer, a plant with damaged roots will struggle to take up enough water. This affects the health of the entire plant and can result in the browning of foliage (especially in evergreens and lawns). A weakened plant is more susceptible to pest and disease damage, and in severe cases, the entire plant may die from winter kill. Because our winters often lack consistent precipitation, many plants will benefit from supplemental winter watering.

What plants benefit from winter watering?

Nearly all plants will benefit from winter watering. However, the following plants are especially sensitive to drought injury throughout the winter.

- Recent Transplants

- Plants that are less established have smaller root systems and need more supplemental water to thrive.

- According to Colorado State University Extension, trees take one year to establish for each inch of trunk diameter at planting.

- Bare root plants take longer to establish than container plants.

- Plants transplanted later in the season take longer to establish.

- Evergreens

- Because evergreens retain their needles, they still transpire throughout the winter. Without adequate soil moisture to replace this water loss, evergreens are at a higher risk for winter burn.

- Evergreens at highest risk include arborvitae, boxwood, fir, Manhattan euonymus, non-native pines, Oregon grape-holly, spruce, and yew.

- To help limit desiccation, some evergreens can be treated with a product such as Wilt Pruf® or Bonide Wilt-Stop®. Read the product label for uses and instructions.

- Deciduous Trees and Shrubs with shallow root systems

- Woody plants with shallow root systems are more likely to dry out because they cannot pull water from deep in the ground.

- These include alders, European white and paper birches, dogwoods, hornbeams, lindens, mountain ashes, willows and several varieties of maple including Norway, silver, red, Rocky Mountain, and hybrid maples.

- Herbaceous Perennials and Ground Covers

- Even established perennials and ground covers can suffer from winter kill, especially those without wind protection and those with south or west exposures that experience more freezing and thawing.

- Lawns

- Newly established lawns are especially at risk for winter kill as well as those with south or west exposures.

When should I winter water?

Most plants will benefit from winter watering from October through March.

According to Colorado State University Extension, water one to two times per month during dry periods without snow cover. Windy or sunny sites (those with south or west exposures) dry out quicker and will require more water.

Only water when air temperatures are above 40°F and the soil is not frozen or covered in snow.

Water mid-day or earlier to ensure the water has time to fully soak in before freezing at night. Test soil moisture before watering by inserting a probe or screwdriver into the soil. If the screwdriver goes in easily, watering is not necessary. However, if it is difficult to push the screwdriver in after a few inches, watering is necessary.

What is the best way to apply water during winter?

While water can be applied by hand, typically it is most efficient to water with a soaker hose, drip hose or sprinkler that attaches to a hose. (Do not use an in-ground sprinkler system as these should stay winterized until spring.)

Trees can also be watered using a deep-root fork or needle that is inserted no deeper than eight inches into the soil in multiple locations throughout the dripline and outside of it. As with watering in the summer, it is important to allow water to slowly soak into the soil. This results in deeper penetration and prevents runoff. For trees, water should penetrate to a depth of 12 inches.

How much water do my plants need?

Mulch is crucial to helping soil retain moisture. The following recommendations assume that all plants have at least two inches of mulch. Keep in mind that most sprinklers deliver approximately 2 gallons of water per minute.

Trees

- Apply at least 10 gallons of water for each diameter inch of the tree

- Water once a month (twice a month for newly planted trees)

- Water from the edge of the branches halfway to the trunk, and then two to three times that distance from the edge of the branches outward

Shrubs

- Newly Planted: Apply at least 5 gallons of water twice a month

- Small, established (less than 3 feet tall): Apply at least 3 gallons of water once a month

- Large, established (more than 6 feet tall): Apply at least 10 gallons of water once a month

- Water within the dripline and around the base

Herbaceous Perennials

- Water requirements vary based on level of establishment and size of the plant

- As a general guideline, apply half the amount of water that would be applied in a typical summer watering session once a month

Lawns

- Water lawns if there has been no precipitation for three weeks and the lawn has a south or west exposure

- Apply half the amount of water that would be applied in a typical summer watering session

Resources

https://water.unl.edu/article/lawns-gardens-landscapes/winter-watering

Rick’s Deer Resistant Plant List

A Note About Deer Resistant Plants

The plants listed here are not guaranteed to be deer resistant. This is merely a guide of what deer generally do not eat. If they are hungry enough, they will eat just about anything, and it can vary from one side of town to the other.

Anything marked with a * indicates plants are browsed occasionally, but typically not destroyed.

The best protection against deer damage is an eight-foot-high fence.

Perennials

Apache Plume (Fallugia paradoxa)

Baby’s Breath (Gypsophilia paniculata)

Basket of Gold (Alyssum saxatile)*

Bee Balm (Monarda)

Bergenia (Bergenia)

Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia fulgida)

Blanket Flower (Gaillardia)

Bleeding Heart (Dicentra spectabilis)

Blue Star (Amsonia)

Butterfly Bush (Buddleia)

Butterfly Weed (Asclepias)

Cacti (Cacti: var genera & ssp.)

Catmint (Nepeta)

Chocolate Flower (Berlandiera lyrata)

Coreopsis (Coreopsis)*

Cranesbill, Wild Geranium (Geranium ssp.)*

Creeping Phlox (Phlox subulata)

Daffodils (Narcissus ssp.)*

Delphinium (Delphinium ssp.)*

Dotted Gayfeather (Liatris punctata)

Dwarf Leadplant (Amorpha)

Globe Thistle (Echinops ssp.)

Euphorbia (Euphorbia ssp.)

False Forget-Me-Not (Brunnera macrophylla)

Flax (Linum ssp.)*

Forget-Me-Not (Mertensia ssp.)

Foxglove (Digitalis)

Golden Banner (Thermopsis ssp.)

Goldenrod (Solidago ssp.)

Hummingbird Plant (Zauschneria)

Hyssop (Agastache)

Iris (Iris ssp.)*

Japanese Painted Fern (Athyrium niponicum)

Lady Fern (Athyrium filix-fernina)

Lady’s Mantle (Alchemilla)

Lamb’s Ear (Stachys)

Larkspur (Consolida)

Lavender (Lavandula ssp.)

Leadplant (Amorpha canescens)

Lenten Rose (Helleborus ssp.)

Lily of the Valley (Convallaria majalis)

Lupine (Lupinus)*

Mexican Hat Coneflower (Ratibida columnifera)

Monkshood (Aconitum)

Penstemon (Penstemon ssp.)*

Peony (Paeonia ssp.)

Poker Plant (Kniphofia ssp.)

Poppy, esp. Oriental (Papaver)*

Prairie Zinnia (Zinnia grandiflora)

Prickly Pear (Opuntia ssp.)

Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)

Purple Prairie Clover (Dalea purpurea)

Rose Champion (Lychnis)

Russian Sage (Perovskia atriplicifolia)*

Santolina (Santolia ssp.)

Sedum (Sedum ssp.)

Shasta Daisy (Leucanthemum ssp.)*

Silver Nettle (Lamium)

Sneezeweed (Helenium)

Snowdrops (Galanthus ssp.)

Snow-in-Summer (Cerastium tomentosum)

Snow-on-the-Mountain (Euphorbia marginata)

Soapwort (Saponaria ssp.)

Speedwell (Creeping veronica)

St. John’s Wort (Hypericum)

Sweet William (Dianthus barbatus)*

Sweet Woodruff (Galium odoratum)

Wormwood (Artemisia)

Yarrows (Achillea ssp.)

Yucca (flowers eaten) (Yucca ssp.)

Bushes & Shrubs

Buffaloberry, Silver (Sheperdia argentea)

Burning Bush (Euonymus)*

Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana)*

Cliff Rose (Cowania neo-mexicana)

Coralberry, Hancock (Symphoricarpos x ‘Hancock’)

Currant, Alpine (Ribes aplinum)

Currant, Golden (Ribes aureum)*

Daphne

Dogwood, Redtwig (Cornus stolonifera)*

Euonymus, Winged (Euonymus alatus)

Fernbush (Chamaebatiaria millefolium)

Grapeholly, Oregon (Mahonia aquifolium)

Lilacs (Syringa ssp.)*

Mahonia, Creeping (Mahonia repens)

Mountain Mahagony, Curl-leaf (Cercocarpus ledifolius)

Ninebark, El Diablo (Physocarpus monogynus)*

Oak, Gambel’s (Quercus gambelii)

Plum, Wild (Prunus americana)

Potentilla (Potentilla ssp.)

Pyracantha (Pyracantha ssp.)

Quince (Chaenomeles ssp.)

Rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus ssp.)

Raspberry, Boulder (Rubus deliciosus)

Rose, Austrian Copper (Rosa foetida ‘bicolor’)

Rose, Persian Yellow (Rosa foetida ‘persiana’)

Rose of Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus)*

Sage, Big Western (Artemisia tridentata)*

Saltbush, Four-wing (Atriplex canescens)

Snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus)

Spirea, Anthony Waterer (Spirea ‘anthony waterer’)

Spirea, Bluemist (Caryopteris incana)

Spirea, Rock (Holodiscus dumosus)

Spirea, VanHoutte (Spiraea x vanhouttei)

Sumac, Fragrant (Rhus trilobata)*

Vines & Groundcover

Bugleweed (Ajuga reptans)

Clematis, Golden Tiara (Clematis tangutica)

Clematis, Sweet Autumn (Clematis paniculata)

Clematis, Western White (Clematis ligusticifolia)

English Ivy (Hedera Helix)

Honeysuckle, Tatarian (Lonicera tatarica)

Iceplant (Delosperma)*

Kinnikinnick (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

Pussytoes (Antennaria speciosa)

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Annuals

Ageratum

Angelonia

Begonias*

Cleome

Cosmos (Cosmos)

Lantana

Marigold (Tagetes)

Nasturtium (Tropaeolum)

Persian Shield (Strobilanthes dyerianus)

Portulaca

Salvia

Snapdragon (Antirrhinum)

Tobacco Flower (Nicotiana)

Torenia

Verbena

Grasses

Blue Fescue (Festuca)

Feather Reed (Calamagrostis)

Fountain Grass (Pennisetum)

Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium)

Maiden Grass (Miscanthus)

Quaking Grass (Briza)

Sedge (Carex)

Switch Grass (Panicum)

Bulbs – Fall Planting

Allium (Alluim)

Fritillaria (Fritillaria)

Grape Hyacinth (Muscari)

Hyacinth (Hyacinthus)

Daffodil (Narcissus)

Bulbs – Spring Planting

Calla Lily (Zantedschia aethiopica)

Canna Lily (Canna)

Dahlia (Dahlia)

Dwarf Iris (Iris reticulata)

Gladiolus (Gladiolus)

Lily of the Valley (Convallaria majalis)

Vegetables, Herbs, Fruits

Allium – Chives, Onions, Leeks, Garlic

Basil

Blueberry

Chamomile

Coriander (Cilantro)

Dill

Elderberry

Fennel

Feverfew

Germander

Globe Artichoke

Lemon Balm

Marjoram

Mints

Oregano

Parsley

Potatoes

Rhubarb

Rosemary

Salvia (cooking sage)

Savory

Squash Thyme

Trees

Cherry, Nanking (Prunus tomentosum)

Fir, Concolor (Abies concolor)

Fir, Douglas (Pseudotsuga taxifolia)

Hackberry, Common (Celtis occidentalis)

Hawthorn (Crateagus spp)

Honeylocust (Gleditsia triacanthos var.)

Juniper, Common (Juniperus communis)

Maple, Rocky Mountain (Acer glabrum)

Pine, Lodgepole (Pinus contorta)

Pine, Pinon (Pinus edulis)

Russian Olive (seeds eaten) (Elaeagnus angustifolia)

Spruce, Colorado (Picea pungens)